Now Illegal under International Law?

Kemi Badenoch was at Policy Exchange this week with a speech that set out a clear distinction between her philosophy on international law and that of the Labour Government. She stressed her commitment to

“not championing ever more expansive approaches to international law at the expense of British interests… recognising that sovereignty matters, our sovereignty above all…we have let ourselves be fooled into believing that international law alone can keep the peace. That international agreements or institutions are somehow ends in and of themselves…“International law” should not become a tool for NGOs, and other critics, to advance an activist political agenda through international bodies or our courts.

If international bodies are taken over by activists, or by autocratic regimes like China or Russia, we must use our influence to stop them, and if that fails, we will need to disengage”

So far, so hard headedly realist. It certainly creates clear water between the Opposition and the mentality that believes giving away sovereign territory and paying the receiver for the privilege is a reasonable price to pay for complying with an international court. But does it go far enough in scepticism for the whole concept?

is well known for his identification of ‘luxury beliefs’, which confer status on the wealthy but may not be fully embraced by them, are expressed in a performative way and whose main intention is to signal virtue to convey social status.This applies neatly to the issues forming the boundary lines for the culture wars. In most cases (trans is perhaps the exception), the additional benefit is that the real costs of the beliefs tend to land with the poor. White working class men become metamorphosed into the main holders of privilege. Liberal views on family breakdown are famously expressed by the wealthy and highly educated liberals but not acted on – broken families and the resulting dysfunction are disproportionately concentrated further down the social scale.

Similar considerations apply to the European Convention on Human Rights. The ECHR and the Human Rights Act that enacts it in UK law have made modest careers for swathes of the surplus elite, and enabled a few particularly able ones to hit the jackpot – the current Prime Minister and Attorney General, and Cherie Blair are three good examples.

The most dramatic changes have been in the field of immigration, where the constant expansion of the meaning of articles 3 and 8 have made deporting even the most dangerous offenders from the UK basically impossible. The consequences here, too, are much more likely to be borne by those in the deprived communities where illegal migrants are likely to be living than in wealthy enclaves of the middle classes where the strongest support for the Convention can be found.

The concept is arguably equally useful in international (inter-governmental) law. When governments sign up to international instruments, their audience is a highly selective one. Very few voters care much about foreign affairs at all. There is however a highly motivated and noisy subgroup for certain issues, supported by a range of high status international lobbyists usually with a Holywood star or two in tow

International treaties can impose significant costs, economic or in terms of restricting states’ freedom to act. Countries like Germany and the UK have taken already significant international commitments on the environment and plan to go even further. Given the two countries together barely emit 2% of global emissions, the impact this will have globally will be trivial. But both countries have seen dramatic deindustrialisation – energy costs in the UK have tripled over the past decade, for example.

This strategy is founded on the belief that countries’ example will inspire others to do the same. This is explicitly an claim to moral prestige, based on the assumption that others are similarly motivated. In the event, it looks as if both countries are committing self harm to the general indifference of the wider world.

Traditionally, if you added together global trade figures you come up with a significant net current account deficit, perhaps reflecting a trade deficit with Mars[1]. Imports are easier to count than exports, possibly because of tax evasion.

In the world of foreign policy, by contrast, we see a net global surplus of claimed ‘influence’. Strangely this soft power rarely seems to translate into support when needed. Successive US administrations have been baffled at their lack of influence even over countries in receipt of massive US support, while for middle ranking countries like the UK most members of the public would be astonished at the idea that say German or Spanish public opinion on a matter of UK domestic policy should have any impact on the UK’s actions – so why would we expect any more influence in reverse? When some countries make real sacrifices of money and effort in the pursuit of soft power, there are potential ‘free rider’ opportunities for others that can resist the temptation to cut moral poses of this sort.

There is a second category of international instruments, which countries sign up to surprisingly casually, perhaps in the expectation that they will never face the consequences of the commitments they are entering into. We are particularly prone to do this when it comes to matters of war.

A good example is the Ottawa Convention on landmines. This was the result of a well meaning, long term, campaign by groups who had seen the terrible consequences of anti personnel mines in former combat zones, still dealing out death and destruction many years later. This was a major campaign focus for the late Princess Diana, taken up by Prince Harry in particular.

Rather than focusing on boring rules about mapping and signing minefields, the convention went for a total ban on deployment, use or storage of anti-personnel mines. The convention has been long ratified and is supported by most states in the world – with the exception of those facing actual military threats who generally refused to sign up. The US (and South Korea) thought about the position on the 238km border along the Korean peninsula, India and Pakistan have refused to sign. Russia refused to sign – but Ukraine did so. As a result, Ukraine is the only state so far to have breached the Convention (very sensibly), a fact that is rarely mentioned. Finland’s Parliament is now considering withdrawing from the convention

The other European countries that remain signatories were presumably assuming they would never be in a position where anti personnel mines are necessary to provide area defence, and the lack of which would put soldiers life at risk. Of course with the possible withdrawal of US support for Ukraine, a stable frontline is only now going to be achievable with measures including a massive belt of mines along a frontier over 1200km long. This is likely to require tens of millions of mines – possibly more than currently exist in storage globally. We are not only going to have to leave the Ottawa treaty, we will probably need to invest massively in industrial production of mines too.

The UK has quite a long record of this sort of muddled thinking. In 1928, the UK signed the Geneva Protocol banning the use of poison gas in war. General Alan Brooke was put in charge of home defence during the peak of the threat of German invasion in WW2. In his War Diaries, he is quite open that he intended to use poison gas on the beaches had the Germans ever landed[2].

The International Criminal Court is another contentious area. The US again took a hard headed view from the start, refusing in principle to accept any possibility of a foreign court having jurisdiction over the behaviour of US troops. The UK wanted to make the system work and has been active in providing senior judges. But recent moves against the Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu have caused consternation among political leaders in many European countries.

For me, though, even this clear expansion of the remit of the Court is not the main problem. The very idea of an international court with the power to pursue offenders quite possibly irrespective of pragmatic amnesty measures agreed locally in the interests of social peace is another example of this kind of overreach. We are demanding countries emerging from the worst experiences a nation can face adopt an approach flatly contradicting that which European countries themselves took in living memory. All this because we complacently don’t expect to be facing similar problems again.

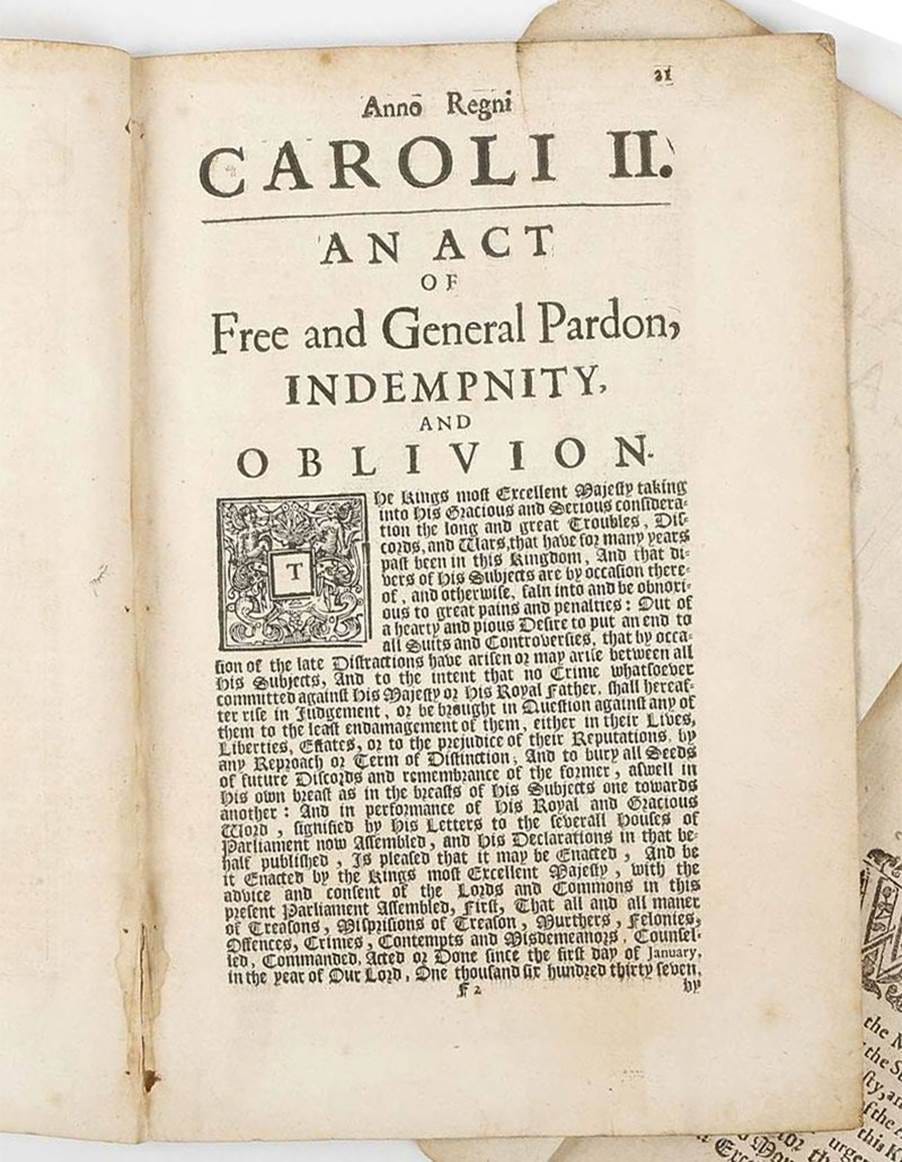

Italy passed an explicit amnesty law in 1946 after tens of thousands had died in an effective civil war. In France, brutal summary justice around Liberation involving probably 10-15000 deaths was replaced by a judicial process of which became progressively more lenient over time, while crimes of the resistance were never seriously pursued. In Spain too, parties of both Left and Right agreed in 1975 on the ‘Pacto del Olvido’ (pact of forgetting) around the crimes of the Spanish civil war. Much longer ago in this country, Charles II passed immediately after the Restoration the Act of Indemnity and Oblivion (bitterly described by his Cavalier supporters who had suffered for their Royalism as ‘Indemnity for his enemies, Oblivion for his friends’).

Fiat Justitia Et Ruat Caelum (May Justice prevail, even if the heavens fall) is a nice sentiment for comfortable times, but a tough one to ask others to risk.

There is inevitably going to be a lot of cant about international organisations and law as the idealism meets grubby political realities. One is reminded of Evelyn Waugh’s sardonic remarks at the Nuremburg Trials of the Soviet judge [‘starting guiltily whenever his country’s name is mentioned’][3]. But the continuing enthusiasm for international law is another symptom of a longing to put difficult questions of morality into a purely technocratic framework overseen by the wise.

But do even its greatest adherents take it seriously enough to stick with it if international law came up with a seriously unpalatable answer?

The Iraq invasion is still routinely described as ‘illegal’, and at the time there were endless debates about a second UN resolution, as if nothing could be thought to be legitimate if it had been vetoed by Vladimir Putin or Hu Jintao of China.

It’s not clear if the same deference would be given if the strict application of international law favoured a less fashionable cause. Iran has never recognised the State of Israel. The Supreme Leader has repeatedly called for the destruction of the ‘Zionist entity’ and supported armed attack on Israel from all fronts. Meanwhile, Iran are well on their way to developing nuclear weapons, despite multiple international agreements from the Nuclear Non Proliferation Agreement onwards. Israel, conversely, has never committed itself not to own or use nuclear weapons.

Given the existential background threat, who is to say that in a further escalation Israel might not see the need to use nuclear weapons on Iran, perhaps tactical nuclear weapons to destroy deeply embedded nuclear facilities? At this point we would see an interesting tension between opposition to Israel and devotion above all to the strict letter of international law. One suspects the enthusiasts for international law would see this as the time to rediscover the merits of just war theory, more subjective but better grounded in morality, and reality.

[1] https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2016/february/global-current-account-surplus-trade-other-planets

[2] Alanbrooke War Diaries p94

[3] Letter to Randolph Churchill